A new study looking at the effectiveness of oral nicotine pouches (ONPs) to curb smoking actually says little about their effectiveness.

A new study looking at the effectiveness of oral nicotine pouches (ONPs) to curb smoking actually says little about their effectiveness.

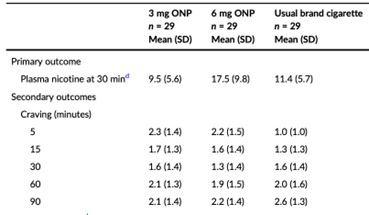

Researchers at Ohio State University compared plasma nicotine levels and subjective nicotine cravings in 30 smokers after the participants had abstained from nicotine for 12 hours and then either used their preferred cigarette, a 3 mg ONP, or a 6 mg ONP.

The authors found that the 3 mg and 6 mg ONPs resulted in a more gradual delivery of nicotine and, consequently, a more limited effect on the study participants’ nicotine cravings as evaluated at five minutes after use. This finding led the authors to conclude that ONPs “might not be strong reduced-harm substitutes” for cigarettes.

Source: Addiction medical journal

Wrong comparator?

The study opted to compare ONPs to smoking rather than to no nicotine use. It’s well established that drugs consumed through smoking or inhalation have a quicker onset of action – and therefore a greater “addiction liability” – due to a closer relationship between their consumption and the resultant psychoactive effect. So it’s no surprise that a cigarette will more quickly reduce a nicotine craving than a nicotine pouch.

However, that’s not the same as saying ONPs do not have an effect on nicotine cravings. Some relief is better than no relief, and for the smoker making a conscious decision to quit, and who wants to abstain from smoking, it is likely ONPs provide some relief from withdrawal. This study, however, forces ONPs to go head-to-head with cigarettes. This means that for the ONP to be successful in the eyes of the authors, its relief must be as good as (or better than) cigarettes.

Results largely ignore later effects on cravings

Media coverage of the study claims its results show that ONPs “do little to curb current smokers’ nicotine cravings”.

This claim arises from the authors’ focus on evaluating cravings five minutes after use. As discussed, the more proximate a psychological effect is to the stimulus that causes it, the more likely the person will develop a behavioural “addiction” in response.

However, somewhere between zero and ten minutes later, craving levels equalise among the products (no statistical difference). In analysing the study, it may be fair to give greater consideration to the earlier times – given their role in the behavioural aspects of addiction – but it seems unfair to conclude that ONPs provided little or no relief, when craving levels are statistically indistinguishable after, at most, ten minutes.

Think about what that would mean if ONPs truly did “little” to curb cravings. If ONPs provide a statistically similar level of relief as cigarettes do 15 minutes after exposure and they provide little craving relief, then a smoker who had a cigarette 15 minutes ago is essentially as likely to crave a cigarette as a smoker who had one twelve hours ago.

Rather than declaring a result now, as is the case with most issues in the area of nicotine research, more research is needed to see how, and to what extent, ONPs curb cigarette use relative to nicotine abstinence.

– Clayton Hale TobaccoIntelligence contributing writer

Photo: Agê Barros